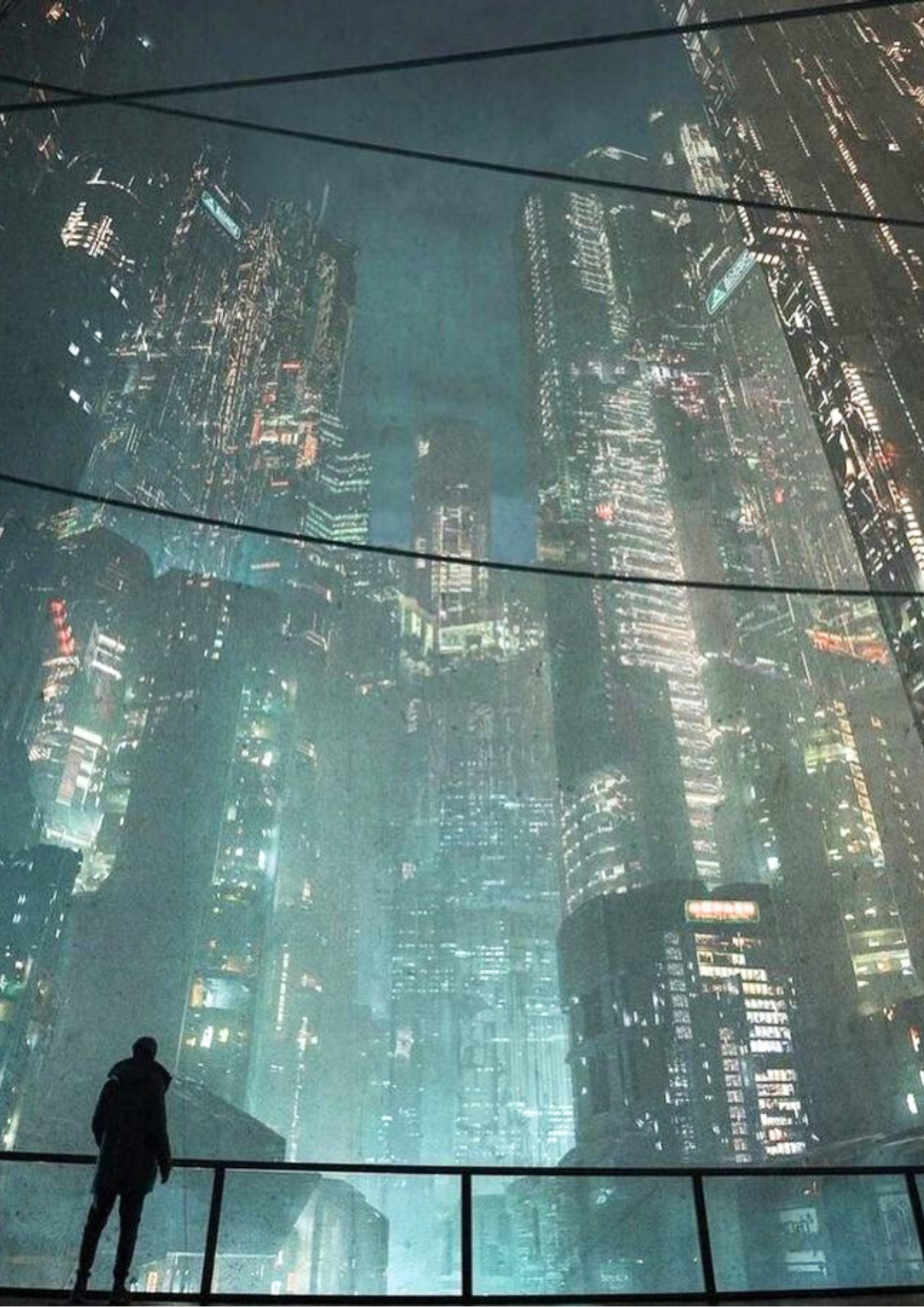

Peace. Order. A perfect world.

Or so it seems. Beneath this beautiful surface—polished to a shine so blinding it almost convinces—lurks something shadowed, something deep. Control. Manipulation. Violence that whispers where it can’t scream. This is how most dystopian stories are structured. From Orwell’s 1984 to Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, dystopian stories don’t merely create false backgrounds and imaginary scenes. They’re a reckoning, decoding our world thread by thread until the truth stands bare. Dystopian literature peels back the layers of reality, exposing the insidious battle for power and control. It forces us to see what we would rather leave hidden in the dark.

A World of Secrets

The one thing present in every form of dystopia is control. In Orwell’s 1984, the Party’s surveillance is not just omnipresent—it’s a silent god, watching, consuming, ensuring that every thought bends to conformity. 1984 feels distant, almost too exaggerated, until you look around and realize you have been watched as well: your clicks, the ads you’re shown, every word whispered in privacy, each fragment of the life that you live on autopilot. Big Brother is watching you, too.

In Huxley’s Brave New World, control doesn’t wear the face of fear but of sweetness. It’s pleasure that numbs the spirit, while happiness and stability are created by The World State through soma—a pill which dulls any pain and discomfort. That’s how they keep society under control.

But the “soma” of our generation isn’t just a pill.

It’s a screen. Algorithmic happiness.

Why We Play Along

The Handmaid’s Tale isn’t terrifying by chance. It’s terrifying because it closely mirrors our own reality. It shows how quickly we can conform to the allure of a better world, built on religion, hope, and fear. We become docile and domesticated citizens, accepting things we don’t fully understand simply because we are told to. Gilead may be a fictional place, but it’s made of the darkest moments of our history. Margaret Atwood reminds us that every atrocity in her book has already happened some time in history. The Handmaid’s Tale feels so real because it is real, echoing what humanity has and continues to go through, time and time again.

In The Hunger Games, the Capitol’s excess is a contrast to the despair of the districts. Suzanne Collins portrays a world where the luxury of a few feeds off the suffering of many. It doesn’t feel like fantasy, does it? It’s more like a convex mirror turned toward our own reality, where wealth and privilege will always shine brighter.

All of these stories have something in common. They’re more than just fiction. They’re questions. Uncomfortable, insistent questions. Why do we tolerate systems that harm us? How much are we willing to sacrifice for the illusion of safety or the bare thread of survival? Is it all about control? And when the reckoning comes, what will we find we’ve already lost?

The Loneliness of Resistance

The most powerful detail in dystopian literature is how loneliness is built around the main characters. To defeat the system and regain freedom, they must go through the isolation that comes with resistance.

Yet, amidst the despair, dystopias teach us about resilience. These characters, imperfect and broken, remind us that change is not about being invincible. Breaking patterns that hold us back isn’t always about the grand gestures, rather it begins with having the audacity to hold onto hope, even when it feels like a faint light in the darkness.

It’s in this fragile breath that dystopias find their soul: the reminder that, no matter how harsh reality may be, hope is an act of resistance.

Leave a comment