Art and artists have been around since the dawn of humanity, from cave paintings to fertility sculptures that have added value to material culture all over the world. But just as artists have been there for mankind, support has been necessary to maintain the pursuit of these arts.

Patronage and sponsorship, defined as the practice of providing financial support to groups or individuals, represent a heavyweight when it comes to the support of the arts and artists alike.

The term “patron” derives from the word “patroun,” which signifies a protector or advocate. This concept implies the use of sovereign power to support another party. In this context, it refers to the relationship between a skilled creator and a powerful figure, such as an individual or corporation.

Art patronage has had significant involvement in the development of the arts across history. From the ostentatious displays of wealth to partnerships with brands, art funding has been, historically, a way of enriching the culture of each era and, as of today, a way of collaboratively keeping alive said tradition.

The Roots of Patronage in Art History

Diorite Statue of Gudea, Ruler of Lagash, Louvre Museum

One of the earliest records we have of art patronage comes from Mesopotamia in the 20th century BC. Gudea, king of Lagash, would commission statues to portray his image to renowned artists of the time, made of hard-to-obtain material such as diorite. These kinds of sponsorships are recorded proof of the use of arts as a medium of displaying wealth, in which a bond between the ruling class and the skilled artisan would immortalize such customs to future observers. In this bond, the upper classes would be in position to possess the art and use it as a method of showcasing the power only their riches could secure.

This relationship was established with the intent of exchanging resources: patrons offered financial support, protection, and various other resources, while artists contributed their skills and expertise.

Besides being a source of wealth display, art has also been in service of the spiritual realm. Religious imagery has depended on skilled artists to provide the otherworldly essence and superiority of the figures worshipped in many religions, particularly within Christianity and, notably, Catholicism throughout much of history. As the power of the church grew, so did its buying power, allowing it to support talented artists on a grand scale. This patronage added an element of greatness to cathedrals and other religious buildings, transforming the act of creating skilled work into a service for the community and contributing to a greater good.

This correlation between church and art had a prominent presence during the medieval era. But it wasn’t until the Renaissance, that the Byzantine Empire’s style and the abstraction of religious art that adorned churches shifted toward a more representational approach.

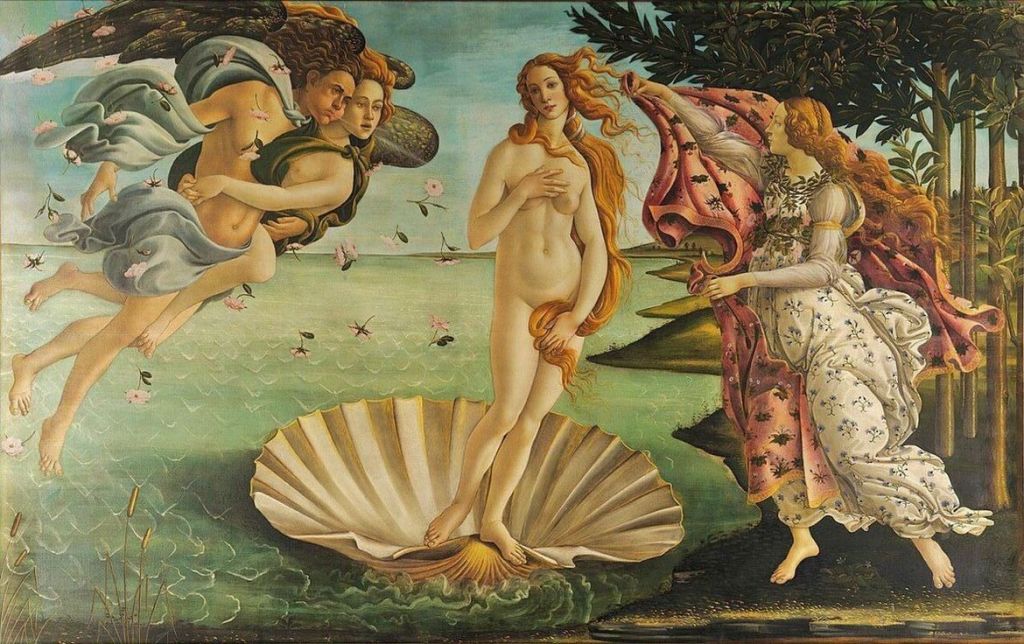

One of the greatest examples of patronage during this time is the relationship between artists and powerful merchants and bankers such as the Medici family. Their patronage which supported renowned masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Donatello significantly contributed to the development of humanities in Florence, Italy. Their wealth helped propel the development of the Renaissance, leading to the creation of masterpieces still preserved and studied today for their artistic significance, such as Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485).

Botticelli, Birth of Venus (1485)

The Renaissance took great steps into more nuanced ways of appreciating and creating art pieces, adding profound representations of religious events and history, while also incorporating portraiture and depictions of everyday life into its repertoire.

Fast forward to the Age of Enlightenment—a crucial time in human history where religious dogma began being questioned in favor of an era of scientific discovery. When it comes to art, this period of history birthed movements like the Baroque, and patronage helped not only display wealth or spiritual attachment but also served as a demonstration of power.

In a distinctive part of Europe, the arts were primarily patronized by absolute monarchs, who monopolized talented artists to serve their courts. For instance, Diego Velazquez created masterful works under the command of Philip IV, illustrating the close ties between royal power and artistic production. In other parts of Europe, however, arts entered the marketplace as a commodity.

As art entered the market more freely, it became accessible to a broader audience, including the emerging middle class. Consequently, the relationship between patrons and artists grew closer, shifting from a mere demonstration of power of the dominated to a more collaborative partnership—patrons became more involved in the creative process, hence establishing a personal bond between them and the artists.

Entering the 20th century, patrons exercised more than ever the usage of their buying power into collecting. Collecting art was less of a display of wealth and instead a way of entertaining the self. However, as the world wars broke out, hiring artists to depict pieces of patriotic propaganda also became more commonplace.

Today, support for the arts primarily comes from foundations and organizations dedicated to funding creative projects. Moreover, digital platforms like Patreon and Kickstarter have revolutionized how we collaborate on and financially support artistic endeavors. Similarly, the rapid growth of digital and influencer marketing has made brand and corporate sponsorships increasingly relevant in recent years.

The Shift to Modern Sponsorship Models

Just as art patronage was the union between benefactors and artists to exchange resources (money/skill), corporate sponsorships speak more of a quest toward co-marketing or a union of influences between markets.

A good example of this are brand collaborations that unify creatives with corporations in order to mutually generate buzz over each other’s products or services, for example, Louis Vuitton collaborating with artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Murakami.

LV x Yayoi Kusama (left) and LV x Murakami

Photo: Courtesy of Louis Vuitton

Speaking of Louis Vuitton, it is worth noting the Fondation Louis Vuitton, a building designed to promote contemporary arts by providing artists and creators a dedicated space for their visual art and presentations.

The association between brands and the arts benefits both parties by providing visibility and generating monetary earnings for artists. On one hand, artists gain exposure and financial support, while on the other, corporations enjoy advantages such as enhanced brand image, access to new audiences, and the opportunity to develop their brand narrative.

Therefore, some of the key differences between patronage and sponsorship come down to the diversity of audiences. During the patronage era, the artist must cater to the specific requirements of the patron, and it must align to their ideology, religious affiliation, and taste.

Meanwhile, in brand sponsorship, the target audience is broader and aligns with specific market segments. In this regard, the artwork must adhere to the brand’s guidelines and narrative. Therefore, it is essential to collaborate with artists known for a particular style that aligns with the corporation’s objectives, placing emphasis on effective storytelling practices that highlight the partnership.

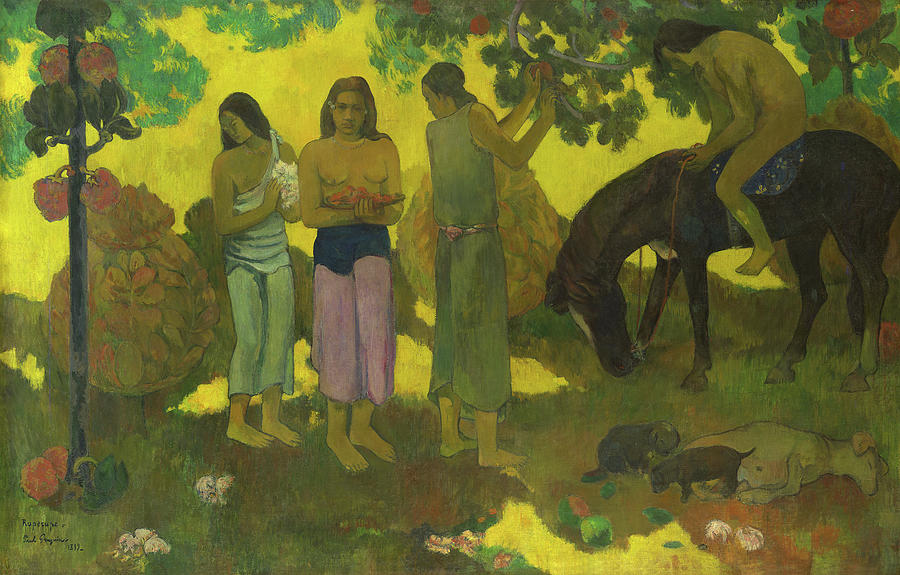

Paul Gaugin in Tahiti, at the Fondation Louis Vuitton

Photo: Fine Art America

Only time will tell what new models of supporting artists will define the century. In the meantime, fostering innovative collaborations, embracing digital platforms, and encouraging diverse funding avenues—like public/private partnerships or audience driven crowdfunding—will be essential to nurture creativity and ensure that art continues to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

References

Art Patronage Through the Ages. (n.d). TEFAF. https://amr.tefaf.com/chapter/history-of-art-patronage#:~:text=Rulers%20would%20often%20sponsor%20art,artists%20of%20his%20day%201.

Komsuoğlu, A, & Kiciroglu, N & Altun, E. (2024). The Patronage of Art: Conceptual and Historical Framework. 10.26650/B/SSc21.2024.028.001.

Lesso, R. (2023) How Did the Medici Family Support the Arts? The collector. https://www.thecollector.com/how-did-medici-family-support-the-arts/

Mann, J. ( February 6, 2016) From Mesopotamia to 1980s New York, the History of Art Patronage in a Nutshell. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/the-art-genome-project-from-mesopotamia-to-1980s-new-york-what-art-history-owes-to-its-patrons

Schumacher, S. (2023). The Artist as the Church’s Mouthpiece: The Cultural Witness of Church Art and Its Patronage. Religions, 14(5), 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050561

Catalina Jahnsen

AUTHOR

Catalina is a scriptwriter, researcher, and communications professional with experience across the media landscape. A true jack of all trades, she has dedicated herself into various facets of the creative industries. Her journey reflects a passion for storytelling, a scholar perspective, and a deep bond to media and arts.

Leave a comment