Truth is slippery.

One thing we can be sure of is that when someone tells us a story, we are not dealing with reality itself. It doesn’t mean we are dealing with a lie. It just means that, at that moment, we are being given access to their version of reality, which is a completely different animal. At that moment, throughout that story, we are witnessing an unreliable narrator as their recital unfolds.

This term, so unfairly and yet so accurately named, was invented by the literary critic Wayne C. Booth in his influential book The Rhetoric of Fiction. Booth argued that in certain narratives, there is an ironic distance between the narrator and the implied author, creating a tension where the reader is invited to question or distrust the story presented.

I have always been fascinated by unreliable narrators. There’s something deeply human about the gap between what we say and what actually happened. We all do it, every day, in small ways. We’re all unreliable narrators of our own lives. But it’s the literary narrators who take this universal human tendency to spectacular extremes.

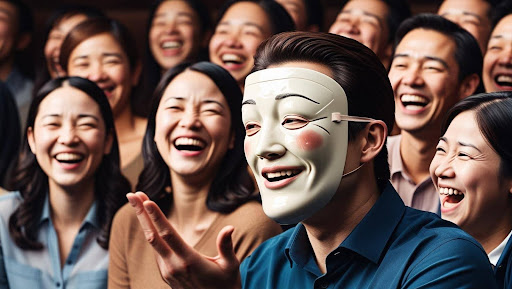

The “I’m Totally Fine” Narrator

Sometimes narrators aren’t deliberately misleading us—they just don’t have all the information. Like Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, who recounts events with the honesty of a child but misses the critical context that we adults immediately grasp.

Reading these narrators is like watching someone trying to complete a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces.

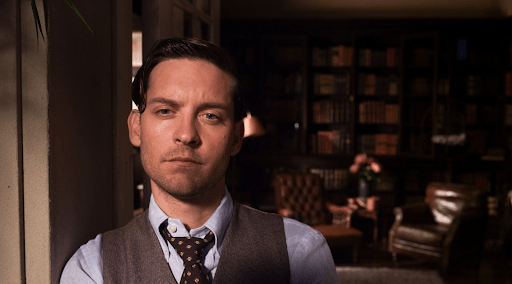

The “Actively Trying to Deceive You” Narrator

There are the manipulators—those who know exactly what they’re doing when they deceive you. They’re playing chess while the reader is playing checkers.

Think of Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby. He introduces himself as “one of the few honest people I’ve ever met,” right before judging everyone else while conveniently omitting his own questionable choices. It’s a masterclass in subtle misdirection.

Or for a more extreme example, there’s Lou Ford in Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me—a psychopathic sheriff who speaks directly to readers with frightening politeness while methodically carrying out brutal murders. He’s not just untrustworthy; he’s a downright psychopath.

The “Reality Has Left the Building” Narrator

While some narrators are actively trying to deceive us, others are experiencing a completely different reality. In Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, we watch a woman’s descent into psychosis through her increasingly disturbing diary entries. The horror lies not only in what happens to her, but in realizing that her perception of reality has become detached from ours.

Patrick Bateman in American Psycho takes this to the extreme, where we are never sure whether his graphic accounts of violence are real or elaborate fantasies. The scariest part is not the violence itself, but the way his mind blurs the line between fantasy and reality until neither we nor he can tell the difference.

The “I Don’t Remember Correctly” Narrator

Memory is unreliable, we all know that, which makes narrators who try to piece together the past inherently suspect. In Atonement, Briony Tallis reconstructs events from her childhood, only to reveal at the end that she was revising the story to atone for a terrible mistake.

What’s especially interesting about these narrators is how they mirror our own relationship with memory. We all reconstruct rather than remember, filling in gaps with what seems plausible rather than what actually happened.

The “Society Doesn’t Listen to People Like Me” Narrator

Some narrators are considered unreliable not because of anything they did or didn’t do, but because of who they are in a biased society. Their unreliability is imposed on them by readers who have been conditioned to disregard certain voices.

In The Color Purple, Celie is a young Black woman in the American South who has been abused and silenced for much of her life. Her letters to God are written in unpolished, uneducated language, and because of her trauma and lack of confidence, she often questions her own worth and perspective.

Readers may initially doubt the depth of her insight because society has taught us to overlook voices like hers — poor, black, female, and victim of abuse. But as her story unfolds, we realize that her way of seeing the world, though shaped by oppression, carries profound truths. Her “unreliability” is more about how society sees her than about any flaw in her perception.

These narrators challenge us to examine our own biases about what stories we believe and why.

Why All This Matters More Than Ever

In times when we’re constantly bombarded with narratives about everything from politics to pandemic response, each competing to gain our attention, understanding unreliable narration isn’t just literary analysis; it’s a survival skill.

When we encounter unreliable narrators, we practice a form of critical thinking that extends far beyond the arts. We’re learning to ask: Who’s telling this story? What are they leaving out? How does their perspective shape what they see?

Perhaps most critically, we’re confronted with the uncomfortable truth that we are all unreliable narrators in our own way. None of us perceives reality perfectly, clearly. We have blind spots, biases, self-protective fictions. And that, I think, is the true gift of the unreliable narrator: not just great storytelling, but a deeper understanding of the story we’re living together.

Vivian Loreti

AUTHOR

Vivian is a writer, designer, and art enthusiast. She has a knack for turning her intrusive thoughts into paper craft and her daydreams into stories. She’s taken a few wrong turns, chased ideas down dead ends, and occasionally forgotten why she walked into the room, but it all somehow ends up on a piece of paper. She loves all things creative and can’t wait to share what’s brewing in her mind.

Leave a comment