Political satire comes in many shapes and forms. It’s one of those sides of humor where the author’s bias is most noticeable compared to others. One of the ways creatives have found to make political satire more comprehensible and easier to digest is through anthropomorphism.

Anthropomorphism refers to the attribution of human characteristics to non-human beings, a well known example of this are the humanized animals in cartoons or in literary works such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

The extent of the personifications vary from work to work, and in political satire, it is a useful tool to simplify ideas while critiquing complex concepts such as power structures, international conflicts, and growing perspectives of the society as a whole.

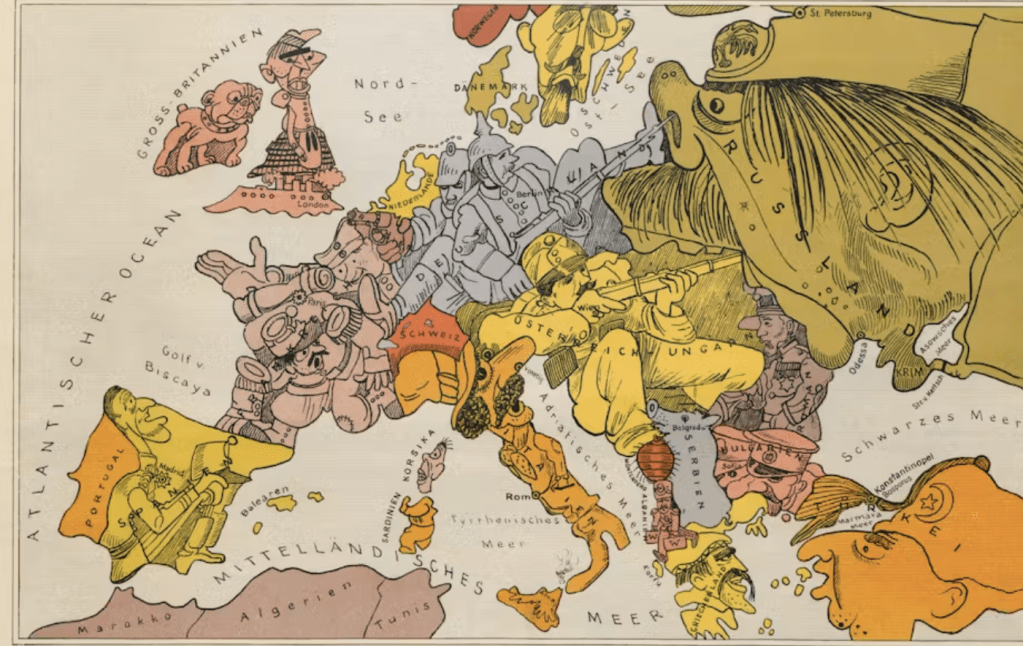

The History of Anthropomorphism in Political Satire

Historically, political cartoons have always relied on figurative speech to portray the behavior of different groups. For example, the image of Uncle Sam is widely known as a portrayal of the United States, having been born after the war of 1812 and could be interpreted as embodying either the nation itself or the government’s actions.

These representations often go hand in hand with propaganda, as they clearly communicate the political ideals the author wants to express through their art. National personifications are usually depicted as attractive, victorious, and even holy versions of the nationality, shaped by the ideals of the society and culture they represent—like Mother Russia or Britannia for the United Kingdom.

However, when it comes to satire, less than desirable traits get utilized by authors to depict national figures, using caricature to make their political critiques more accessible to audiences.

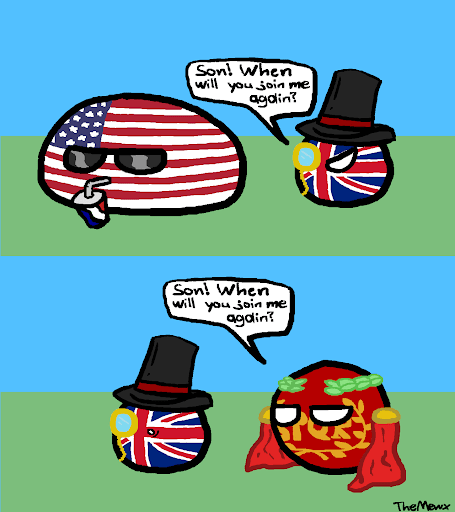

In the modern era, it’s especially common to find personifications of different nationalities. We have the countryballs, webcomics made by different artists online, where countries are represented as circles painted with their specific flags, given eyes and the ability to speak, mostly used to illustrate different moments in history and modern international relations.

There’s Hetalia, another webcomic turned manga, turned anime by Hidekaz Himaruya, where each country is portrayed as a fully human form living through various historical events. There’s also Countryhumans, which works similarly to countryballs but features more humanoid physical traits and rounded faces. And so on—many other examples can be found in the digital age.

Simplification vs. Oversimplification

Anthropomorphism for satire introduces a conundrum. How do we deal ethically with simplification to not fall into oversimplification? After all, while anthropomorphism makes both historical and current political events relatable and easier to empathize with, there is an inherent risk of depending on stereotypes that can reinforce biases within audiences. By making a country into human form, there’s a limited amount of representation that can be portrayed at the same time.

The problematic nature of anthropomorphism comes, mostly, from the biases of the corresponding authors and what they want to represent through the media they produce.

Hetalia, for example, tries its best to stay away from extremely controversial, modern day situations after a problematic comic strip was made regarding the Japanese-Korean territorial dispute over a group of islands, showcasing Korea, a character portrayed as a loud and obsessed over Japan, touching Japan’s nipples which represented said islands. Making the Korean character banned in South Korea over the offensive representation, giving the author a nationalist reputation.

Other webcomics, such as countryhumans, fall into similar problems, but multiplied by 10. Each comic is made by random creators on the internet, with no plot or permanent personification, leading to offensive content being created with less risk of backlash thanks to the anonymity of the internet, enabling the creation of comics that showcase real life tragedies in a lighthearted manner.

The Role of Anthropomorphism in Building Empathy

History is mostly horrifying—an endless source of war, famine, and destruction, both recorded in books and unfolding in real time. Anthropomorphism is usually utilized to foster understanding across cultures, commonly by portraying the leaders of a country as personifications of either the government’s or the people’s interests. This provides a quick way of generating understanding and context for the masses.

Humor comes, in part, from self-awareness; recognizing both the good and the bad creates a clear ethical narrative. We laugh at the horrific things Eric Cartman from South Park does because we understand they are morally reprehensible. In the same way, our collective beliefs help shape our sense of humor, and satire takes hold of that.

Anthropomorphism in comedy can be done in good or bad faith. Good faith would be an attempt to foster empathy in audiences, where stereotypes are used as a way to convey a message in the simplest form. On the other hand, there are racial caricatures that purposely portray negative stereotypes to make audiences laugh at the people, rather than at the terrible things around them, missing the opportunity to bring awareness or promote resilience.

Now the question is, does anthropomorphism humanize international relations or trivialize them? The question is impossible to answer as it all varies from artist to artist, and on some level, from audience to audience. But it does give us some segue into reshaping history through relational storytelling.

The duality of anthropomorphism, as both a powerful tool for satire and a practice fraught with ethical considerations, makes it especially important to consume this style of comedy with a critical eye. We can enjoy the humorous depictions of nations and political entities while also recognizing that the content is inherently biased and limited.

Leave a comment