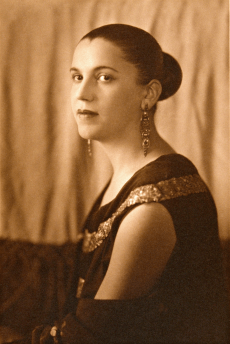

Tarsila do Amaral

The Artist Behind the Paintings

Tarsila do Amaral was born in 1886 on a farm in São Bernardo, a rural area of São Paulo, Brazil. Coming from a wealthy family, her father, José, and her mother, Lydia, belonged to traditional and affluent lineages. Her grandfather, who shared his son’s name, owned numerous farms in the region and was often referred to as a “millionaire” due to his wealth.

Tarsila spent her childhood amid the scenic beauty of these farms, surrounded by lush green hills and nature. She began her education in Brazil but completed it in Barcelona, Spain. At the age of 16, she created her first artwork, titled “Sacred Heart of Jesus.”

In 1906, Tarsila returned to Brazil, married, and started a family, giving birth to a daughter. Despite her new responsibilities, she continued her art studies. In 1920, after her divorce, she moved to Paris to study at the Julian Academy, a prestigious school for painting and sculpture.

Two years later, after refining her artistic style and meeting various painters, including Émile Renard, a classmate, Tarsila had her works featured in the Official Salon of French Artists. That same year, she returned to Brazil and began to engage with the burgeoning Modernism movement.

A Tour to the Modernism Era in Brazil

During her studies and experiences, Tarsila encountered a world vastly different from the one she had known growing up on the farm. She was introduced to urban life, exposed to diverse perspectives and experiences. At that time, Brazil was home to many local artists eager to revolutionize the art scene.

Politically, the country was facing tensions among the major European powers while transitioning from the Old Republic to the presidency of Getúlio Vargas. This era was characterized by its transgressive, anti-academic, and nationalist sentiments in Brazil.

A key event symbolizing Brazilian Modernism was the “Modern Art Week”. Held from February 13 to February 17, 1922, this event showcased a variety of artistic disciplines, including dance, music, poetry, art exhibitions, workshops, and sculpture.

Tarsila was a prominent figure in organizing this event, alongside four other modern Brazilian artists: Anita Malfatti, Menotti del Picchia, Oswald de Andrade, and Mário de Andrade. Together, they formed a group known as “The Group of Five,” which played a crucial role in establishing the Modern Art Week and, subsequently, the Modernist Movement.

The defining characteristics of this movement, evident in each artist’s work, included:

- A rejection of the classical norms of traditional painting

- The use of bright colors and geometric shapes

- The exploration of social themes, everyday life, and Brazilian landscapes

- The creation of a unique visual language reflecting Brazilian heritage

In my view, the Modernist movement in Brazil represents one of our golden eras in art. It celebrated the vibrant colors, authentic lives, and diverse cultures that define our country, affirming that these elements can also constitute art.

Tarsila’s Unique Way of Painting

Tarsila’s art is distinguished by unique colors, themes, and styles. She often selected vibrant palettes, including blue, yellow, and green, as a nod to Brazil’s flag and cultural heritage.

Her works exude vitality; she loved capturing Brazilian life, whether through depictions of our society or natural environment.

To her, identity was paramount.

Tarsila employed unconventional techniques to bring her concepts and colors to life, drawing influences from Cubism and Surrealism. Let’s explore some of her most famous paintings:

“Abapuru”, 1928

This piece is often regarded as Tarsila’s signature work. “Abaporu,” which means “man that eats,” inspired the Anthropophagic Movement, a part of the Modernist movement influenced by Surrealism.

The painting features a figure with exaggerated proportions that fills the canvas, symbolizing the “devouring” of European cultural influences in the quest to create something distinctive and uniquely Brazilian.

The figure is depicted sitting beside a cactus, embodying both the welcoming and hostile aspects of Brazilian nature.

“Labors”, 1933

In contrast, “Labors” tells a different story while reflecting similar intentions in representing Brazilian culture. This piece showcases the daily lives of workers and the societal changes brought about by industrialization in Brazil. Notably, “Labors” employs a cooler color palette of grays and blues, emphasizing emotionless faces and revealing the alienation often associated with industrial work.

During this period, this subject was never explored in Brazilian art; once again, highlighting Tarsila’s revolutionary approach.

What makes this painting particularly interesting for me is that Tarsila came from a wealthy family that owned large farms in the countryside of São Paulo. However, her privileged background did not shield her from the concerns of her surroundings and the broader world. Instead, through her art, Tarsila embraced a mission: to portray Brazil as it is—beautiful yet fraught with complexity.

Tarsila’s Last Years and Her Legacy

Tarsila lived during a pivotal period in Brazil’s history when capitalism began to emerge alongside the rise of large industries, leading to serious social problems.

In her personal life, Tarsila had a few lovers. Her first relationship resulted in her only child, a daughter named Dulce. Unfortunately, none of her subsequent relationships flourished. The most heartbreaking affair was probably with Oswald de Andrade, a fellow modernist painter and member of The Group of Five.

Oswald ultimately left Tarsila to marry Pagu, another revolutionary artist of the era. His departure caused her immense pain, as she had to confront not only the loss of love but also the realization that the family farms from her childhood would no longer belong to her. This heartbreak fueled Tarsila’s commitment to her art.

Her last significant relationship was with Luiz Martins, a Brazilian writer, and they dated until her fifties. However, in 1965, her life took a drastic turn when she underwent surgery to address chronic back pain. Unfortunately, due to a medical error, she became paralyzed.

In 1966, Tarsila faced another devastating loss with the death of her daughter Dulce, who had diabetes. This tragedy led her to explore spiritism in hopes of coping with her many losses.

Tarsila passed away in 1973. Today, she lives on through her paintings, which tell unique stories and perspectives about Brazil’s history.

She serves as a symbol of strength and authenticity for female artists pursuing their ambitions and sharing their own stories and visions without fear of conforming to traditional patterns. Tarsila reminds us that art does not follow a predefined structure; it simply needs to be alive, telling a story—whether expressed through melody, movement, or a canvas.

Leave a comment